Post

REPORT | Saturday Planning School: The City

9 Oct 2018

The final talk in this year's Planning School was given by Euan Mills (Future Cities) and Professor Mark Brearley (London Metropolitan University). Barry Coidan reports.

Euan Mills is the Urban Planning and Design lead in charge of Future Cities Catapult’s Future of Planning Programme. Euan talked quickly: he had to he had a lot to get in a very short space of time. Technology is changing us, it’s changing how we live, work and interact. It’s changing businesses and how we do business. Where we do business, where we live is more and more in cities. But our cities are analogue, tied down with analogue planning systems. The city environment is changing rapidly driven by digitalisation and big data, but looking at the planning system you’d think the last 20 years hadn’t happened.

Not so long ago the most valuable companies by share capital were those involved in energy, metal bashing and heavy industry. Now those companies have surrendered their place to the data companies. The companies that have grown up in the last 20 years - Google, Facebook, Amazon etc - as we enter the fourth industrial revolution.

Cybernauts, Artificial Intelligence (AI), brought about by the exponential doubling of computer power: this technological thrust is changing the way cities work. Look at Airbnb, started in 2008 it now has over a million beds in cities across the world many more than the Hilton Group founded in the early 1900’s. There’s the Collective offering shared living and working spaces - giving young business people the opportunity to start up without facing crippling office and living costs. Appear Here which began in 2012 now offers rental space of 10 million square feet. Made possible by technology, the internet and social media. By reconfiguring existing space, new business has an opportunity to start and grow.

There are smart meters to monitor your energy use, Hive to allow you to adjust your heating, light and home security remotely. Intelligent speakers link to the internet playing you music, ordering a pizza, booking that theatre ticket. Payphones are being replaced by InLink - a free wireless service from BT. Then there’s big data - zillions of bytes - data on everything and everyone. Cloud computing offering the individual many times the processing power of their own PC - Now you can view a compete revamp of your front room in virtual reality on your iPhone before buying from IKEA.

Virtual Reality and Computer vision allows medical students to get close and personal to the operating theatre without risking a live patient. Autonomous vehicle use object identification to take you (quite) safely to your destination. Police, stores, airports etc use face identification to track visitors. Fed up with millions of white vans dropping off Amazon parcels - soon a drone controlled by GPS will wing its way to your garden or front door and drop of your purchase. There are huge privacy, security issues to be tackled; but the point is the frantic pace of technological change is fundamentally changing the world around us.

The trouble is town planning is stuck in the past.

Most town/city plans are out of date. The policy framework is redundant. Data is analogue with manual collection. Planning officers still tour towns to count the number of new builds. Plans are in pdf format - which is not machine readable. Where there is data it’s inaccessible or poorly signposted.

Data is undervalued or treated as commercial sensitive. Planning processes are poor and opaque - only understood and navigated by experts and planners. Even worse the policies against which decisions are taken are ambiguous. It is no surprise that planning decisions are more often than not politically driven and this leads to poor planning which satisfies no one except possibly the developer.

We need to upgrade how we plan, not what we plan for. How do we achieve this:- By treating planning as an operating system so it is susceptible to data input. Link policy to evidence so that when data changes policies can evolve. Digitalise and geo-locate local planning policies. Standardise digital development proposals. Automate development management processes. Screen digital based proposals against digital based policies and automatically validate planning assumption - e.g. density. In short once you collect and digitalise data it becomes amenable to all the modern interrogative techniques digitalisation and machine learning provide. It’s not complicated- it’s hard slog.

The ingredients for this change is data and agreed standards. The principles to be applied is small and agile along with distributive ownership not monopolies. It would be open and web based. The threat is that those with the data and the capacity will be the ones who build the cities of the future. Already Google knows more about our streets than do planners. Tech Companies have plans to build their own cities. The public sector - representing all of us should be doing that.

The 1947 Town and Country Planning Act was Professor Mark Brearley’s point of departure in his combative talk. That Act nationalised planning rights then gave them back to local developers only when local authorities were satisfied. From day one the Act laid great emphasis on restraint - which was unsurprising given the abuse in previous decades - by outlawing development in the background of the countryside. This was epitomized by the establishment of “Green Belt” - protecting the countryside from unrestrained and unplanned growth.

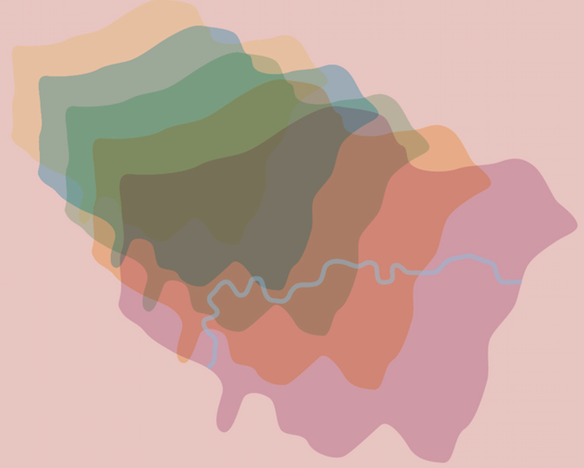

There followed a long period of population decline in London which hid the pressures the Green Belt placed on London but by the end of last century these latent shortages become apparent with London’s success in attracting business and population accelerating at a rate not seen since the 1800’s. Now shortage became critical and was played out through rapid increase in property values and increased inequality. London was eating itself.

In the 1970’s Richard Mayden published the “Unofficial London Countryside” which detailed how the countryside had taken over the city’s old bombed out derelict sites. It struck a chord. These “urban spaces” were recognised as important and were not simply fair game for developers. As a result by the 1990’s we had a London Green grid - the greatest achievement being saving Rainham Marshes. But London was growing, it needed housing yet Green Belt constraints and that of the Green Grid restricted available land. The centralist’s answer was to strip out London’s industrial land - after all London was losing it old industrial base anyway.

Except, the planners had no understanding of London’s industrial economics. More significant than the city wide open spaces - London’s industries provide 500,000 jobs. The neglect of this vital resource has led to a 15% reduction with far too low vacancy rates leading to rapid and killing rent increases.

Local authorities were actively driving out industry to be replaced by housing. Yet there was increased demand from companies to locate within the M25. It’s not a binary choice - housing or industry. With sensible planning, mixed development delivers housing, industry and jobs. We need diversity, a mixed economy but at moment local authorities are deaf to reason.

Mark runs his own business and has experience of local authorities myopia and deafness. His business on the Old Kent Road is threatened by demolition by the la to build housing and his experience of contacts with them is disjointed and opaque. This is not the way to engage with a vital part of his borough’s economy.

During the Q & A session Euan was asked why planning processes hadn’t moved on. He suggested part of the answer was because local authorities were signed up to long term legacy systems contract. Old systems, old procedures which locked in la’s. This restraint is now being recognised within Government. The Cabinet Office’s “Government Digital” is seeking to redesign the way Government does business - don’t hold your breath.

A question that got to the heart of the conflict between the individual and planners was whether you could build in a way that people were happy with but worked against the system. Euan said that we can measure the potential impact of a development but that’s not been explored so it’s currently down to personal choice or that of the Planning Committee.

Mark was asked about arguing against a housing development and maintaining, say, a historic 1920’s industrial site, with the potential of seeding small businesses. It was hard - short term political gain - housing (even if unaffordable) against one (wo)man small businesses. Mixed development - it’s possible for small businesses to co-exist within a large residential development.

But the system is off centre. Don’t blame businesses for the mess - it’s planning restraints. Build a school, designate an open space and you’ll get grants galore. Businesses don’t have the vote so politically they don’t have a say, they don’t get the breaks. That needs to change if we’re to have a vibrant, wealth generating economy for London.