Post

ARCHIVE | The birth of the conservation area

20 May 2020

In this article from Journal 471 (Spring/Summer 2017) Frank Kelsall considers 50 years of the Civic Amenities Act, and the events that led to its creation.

The Civic Amenities Act of 1967 introduced conservation areas into planning law. Although some have chafed at the additional restrictions on development, the act has proved one of the success stories of British planning. The definition of a Conservation Area as ‘an area of special architectural or historic interest the character or appearance of which it is desirable to preserve or enhance’ has been both a restraint on inconsiderate proposals in areas with a distinct character and an encouragement to thoughtful design.

The ideas embodied in the 1967 Act can be traced back to earlier planning acts and a rising concern about townscape: how to deal with characterful areas where the buildings themselves might not be of special interest? The compilers of the first lists of historic buildings were instructed to include the now obsolete (and non-statutory) grade III buildings, which had a cumulative group or character value. But simple listing was not enough.

London's first conservation areas

The London County Council (LCC) used the powers in the 1947 Planning Act to widen building preservation beyond the individual monument. In 1959, when a block of buildings in Westbourne Terrace, Paddington, was threatened with demolition, the LCC served a building preservation order (BPO) on the whole of the terrace and some of the approaches to it, more than 160 buildings in all. W A Eden, then architect in charge of historic buildings for the council, said in evidence to the public inquiry that the threat to the part constituted a threat to the whole.

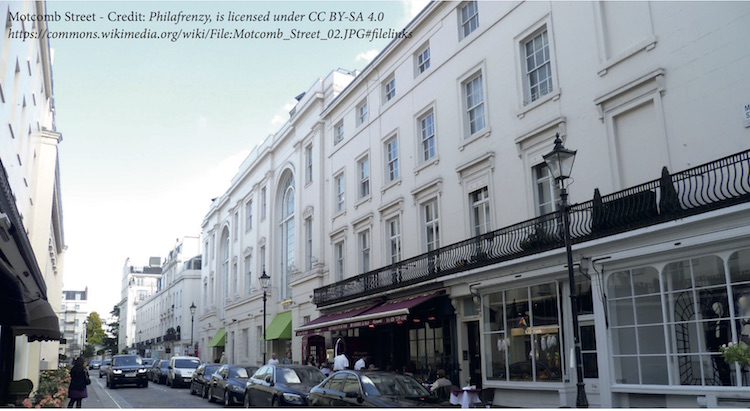

Such local action had to be backed up from the centre. So it was – by the confirmation of the Westbourne Terrace BPO and again a few years later after a public inquiry over Motcomb Street and the Pantechnicon in Belgravia. Here the inspector had advised that only one side of the street should be kept, but he was over-ruled by the Minister who confirmed the council’s order on both sides of the street and adjacent buildings.

Introduction of the act

The Civic Amenities Act was introduced into Parliament as a private members' bill by Duncan Sandys, founder of the Civic Trust and one-time Minister of Housing and Local Government; he gained the government support that saw his bill into law because he incorporated into it the government’s own ideas on area conservation.

That support was largely due to Richard Crossman, the minister, who had set up a Preservation Policy Group in 1966 and commissioned reports on four historic towns – Bath, Chester, Chichester and York. The group’s report and these area studies were the basis of policy developments in the 1970s, strengthening the legal framework and widening the availability of financial support.

These studies show that perhaps London was not at the forefront of government thinking, or was already able to look after itself; London was, however, in the vanguard of conservation area designation. Eighteen months after the 1967 Act became law, there were 210 conservation areas in England, 52 of them in London. The new London boroughs, formed in 1965, took the initiative, preparing a development plan for the whole metropolitan area. The Greater London Development Plan of 1969 is now most remembered for its hugely controversial ringway proposals that would have demolished areas such as Covent Garden, but it also included conservation policies.

The new Greater London Council, building on the work of its predecessor the LCC, set about surveys of areas – especially the great historic estates – where it was likely that conservation areas would be most appropriate. In 1973, after public inquiry, Minister Geoffrey Rippon accepted the need for comprehensive redevelopment in Covent Garden but rejected most of the GLC’s ideas for achieving it, at the same adding nearly 250 buildings to the statutory list. Since then, conservation has been a fundamental consideration in London planning.

Fast forward to 2017

So where are we now? At the latest count there are just over 1,000 conservation areas in Greater London, about one tenth of the national total. They vary enormously in size and character. Some boroughs are now extensively covered: Kensington & Chelsea has 38 areas, including the large Ladbroke neighbourhood, and many immediately adjacent to each other; Lambeth has 62 areas covering 30 per cent of the borough. Others have fewer: Barnet has 17, which includes the substantial Hampstead Garden Suburb Conservation area. Barking & Dagenham has just four. Some areas need dual designations because they overlap borough boundaries – Highgate and Blackheath are notable examples.

Local planning authorities have a statutory duty to consider designations; at present new ones seem unlikely, though many are being amended in the process of review. is may in part reflect a feeling that a limit has been reached, but it also follows the difficulties of local authorities in adequately resourcing

the areas they already have. The number of conservation officers has declined by one third in recent years, and their efforts are largely directed to producing the appraisals and management plans that current policy demands. This problem can be seen acutely in Hillingdon, for instance, where there are 31 conservation areas, many covering old village centres, long under threat from Heathrow expansion, but of these only five have appraisals and only two management plans.

Where an area retains most of the buildings and a residential character with which it was first developed, conservation policy is usually straightforward. Preservation usually means keeping the buildings as intact as possible and enhancement often means improving the public realm. But where ‘character’ derives from piecemeal development over many centuries, as in old high streets or former village centres, the problem is more difficult. Should this process of continuous redevelopment be brought to an end? If not there are hard decisions to take: should new interventions merely preserve the character of an area (established by the courts as meaning ‘doing no harm’)? Or should they seek enhance by more radical new design that will, in time, become accepted as part of the character of an area?

The case of the City

This question is particularly acute in the City of London. Here there are 26 conservation areas, some quite small and tightly drawn; the largest is Bank CA, over 50 acres; the smallest, Crescent. The City has decided that no more than a third of its area should fall within conservation area controls. Compared with most London boroughs, the City is well resourced and 17 of the 26 conservation areas have up-to-date appraisals and management plans.

While control over works in the areas is carefully considered, large new buildings just outside can have overbearing effects, effects not always restricted by the protected views of St Paul’s. In some small areas, new works can represent a radical change to the whole – in Crescent, about half the area is affected by the new building by Tower Hill Station.

In the 50 years since 1967, the City of London has changed into a different city, in many ways a livelier place with more active street frontages and increased permeability. New buildings are usually better designed than they were in the 1960s; it is often the more recent buildings that are targets for redevelopment.

The public realm has been improved and matters such as signage and advertising in conservation areas are well considered. But it is di cult to resist the conclusion that 50 years of conservation area control have not halted the City’s progress towards Manhattan-on-Thames.

Frank Kelsall is an architectural historian and former Chair of the London Society; he is the Society's nominee to the City of London Conservation Area Advisory Committee.