Post

ARCHIVE | Boom Town: previous London population explosions

6 Apr 2020

While London is experiencing a significant population spurt in percentage terms, it’s not the largest rate of growth in our history by any means. Michael Paterson of London Historians looks at the impact of the capital's previous population explosions.

(From The Journal of The London Society issue 470 - Autumn/Winter 2017)

Londinium

There is good archaeological evidence of human habitation around the Thames prior to the arrival of the Romans; artefacts from the period can be seen in the prehistory galleries at the Museum of London. The first significant settlement in the area, occurred only after the Claudian invasion of 46AD, and even then it came in stages. Initially a garrison and bridge from 47 until its destruction by the Iceni under Boudicca in 60/61, Londinium wasn’t developed by the Romans as a fully-functioning port and trade centre until the 70s onwards.

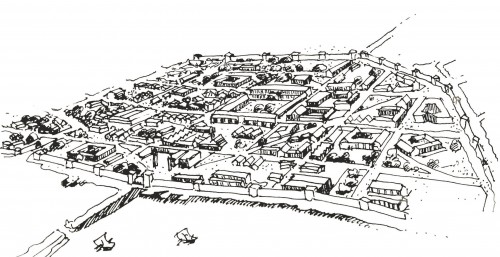

Rapid development followed for the next 70 years or so, characterised primarily by the port with attendant warehousing, but significantly also a forum, squares, temples, a basilica, amphitheatre and sundry civic buildings: in short, all the trappings of a Roman imperial centre, making Londinium de facto Britannia’s provincial capital. At its height circa 122 coinciding with Hadrian’s tour of the province, it is estimated the population of London was at least 45,000 and possibly as many as 60,000.

What does this signify for that period? Rome’s population at that time has been variously estimated at between 400,000 and near to a million. Agreed, that’s a huge margin of error. Nonetheless, we can probably say that Londinium was about a tenth of the size of its mother city. That’s a significant size for the period with only a handful of others – such as Alexandria and Antioch – being larger.

Archaeological evidence indicates Londinium suffered a major fire soon after Hadrian’s tour. At some stage in the late Roman period it was re-named Augusta, but this epithet for a provincial capital could not disguise the city’s decline. A er the legions abandoned Britain and as the Roman Empire in the west disintegrated through the early fifth century, Londinium’s raison d’etre as a bustling port and trading hub evaporated. London’s population didn't recover its size for another thousand years.

For the next several hundred years, London was little more than a ghost town, even taking into account the settlement of Lundenwic; roughly in the area of Covent Garden and the Strand today. It was not until Alfred the Great restored the City in the 880s that London began its slow return journey, first to significance and then ultimately to pre-eminence.

Tudor London

Barring the calamitous setback caused by the Black Death in 1347, London’s population grew at a steady but unremarkable pace during the late medieval period to around 50,000 inhabitants. Then, from the final years of Henry VIII’s reign until the end of Elizabeth’s in 1603 it increased fourfold, reflecting that of the nation as a whole.

The period saw major economic improvements in manufacture and trade, particularly in finished goods. The foundation of independent joint stock companies and the rise of a more ambitious and confident mercantile class, personified by men such as Sir Thomas Gresham, combined to create a vibrant financial environment in London to rival, for the first time, the by now diminished Northern European cities of the Hansa. Gresham founded the Royal Exchange in 1571, London’s first bourse modelled on that in Antwerp. He and other like-minded City merchants encouraged the queen to cancel centuries-old foreign trading and banking privileges culminating in the closure of the Steelyard (a closed German trading district of offices and warehouses near today’s Cannon Street Station) in 1598.

In the meantime feeding into this revitalised London, England had more mercantile ships on the high seas than ever before. Many of these were of dubious status, as we know, depending on the needs of the Crown at any given juncture. e upshot of this mercantile frenzy was large- scale migration to the city both from all over England and indeed, abroad. London quickly became extremely densely populated, noisome, smelly, overcrowded. Various ordinances failed to prevent ribbon development along major trunk roads outside the walls. But for the first time in its history, London had arrived as a global city.

London’s rapid population growth continued into the 17th century. Despite the English Civil War and four major outbreaks of the plague (1603, 1625, 1636 and 1665), the city’s population more than doubled to well over 400,000 by the century’s end, eclipsing Paris for the first time. London had been a fraction of the size of the French capital throughout the middle ages. at now had changed forever.

19th Century

Between 1825 to 1914 – approximately post-Napoleon to the First World War – London was the capital of the most comprehensive trading empire in history, and the world’s largest city. It saw a period of explosive population growth. From around a million denizens in 1800 it expanded over sixfold in the following hundred years.

The causes were manifold. Early in the century, the national canal system finally joined up properly with London as simultaneously virtually all her main deep basin docks were completed. is process had barely played out when the railways arrived, first the great termini, then the Underground. Simultaneously, and no less than in Birmingham and Manchester, steam-driven industrialisation transformed the landscape, particularly to the east. As in previous times the demand for workers was fed by immigration rather than natural growth. thousands flocked in from all over the country and Europe, with notable influxes from Ireland after the famine and in the 1880s with pogrom-fleeing Jews from Russia, Poland and Germany.

The inevitable consequence was squalor, overcrowding, disease, pollution and widespread grinding poverty. The problem was endemic through the capital but particularly bad in the East End, St Giles, Clerkenwell and Westminster. Parishes, housebuilders, reformers or charities: nobody could outpace London’s population explosion in the Victorian era.

London’s population hardly grew throughout most of the 20th Century. Although that seems to be changing, it’s highly unlikely we will again experience the huge booms of previous times.

Michael Paterson is the Director of London Historians