Post

Artists, gentrification and property in London

7 May 2024

When Peter Carty was researching his novel Art, about the birth of the Young British Artists in Hoxton and Shoreditch in the 1990s, he discovered that the area’s associations with rebels and contrarians goes way back.

My novel Art is all about the birth of the Young British Artists in Hoxton and Shoreditch during the early 1990s. I lived locally and witnessed the creative explosion that took place when the artists arrived. They helped kick-start the enormous gentrification of the area that is the backdrop to the novel.

But as much as the artists flouted social convention and rebelled against the art establishment, during my researches I discovered they were merely the latest group of renegades and outlaws to favour Hoxton and Shoreditch. They had notable parallels with predecessors from previous centuries

When I was a resident, the area was something of a no-man’s land. After the office workers had departed for the day, many streets were left largely empty during evenings and at weekends. And it was a similar situation during medieval times. The area was outside the City’s boundaries and honest burghers ensured they were safely back inside its walls by sunset. The gates were closed each night as late as the 1760s. Left outside were those who were barred from entry — or who had barred themselves. They came in many varieties: religious contrarians, rebels and revolutionaries, actors and playwrights, and a large rump of the dissolute and lawless.

Check out our rundown of upcoming events

The name “Hoxton” is derived from the Saxon word “Hochestone”, which means a farm or protected enclosure. Hoxton was in the parish of Shoreditch. By 1601 there were more than 20 houses on Hoxton Street, despite the prohibition by Queen Elizabeth I on new buildings within three miles of the City. Towards the end of the sixteenth century we are told that Hoxton housed “enclosures for gardens, wherein are built many fair summer houses, some of them like midsummer pageants, with towers, turrets and chimney tops, not so much for use or profit, as for show and pleasure”.

But there was more to the area than gardens and follies. Because it was on a major travellers’ route into the City, it hosted entertainments which were banned within the City itself. There were bawdy inns, brothels, gambling dens and bear baiting. Theatrical productions were also deemed immoral by the City administration and banished. London’s first theatre was sited in Hoxton in 1576 on Curtain Road, called simply “The Theatre”.

A young William Shakespeare wrote and acted for it. Romeo and Juliet was first staged there in 1597. Nearby, Ben Jonson killed an actor called Gabriel Spenser during a duel in the courtyard of an inn on what is now Pitfield Street. Jonson narrowly escaped hanging. While the artists of the 1990s frequently behaved badly, they had nothing on this.

The Gunpowder Plot of 1605 was foiled when Lord Monteagle received a letter revealing its details at his residence on Hoxton Street. There is a commemorative plaque at 244-278 Crondall Street, a block of flats that stands near the site. Fast forward to the 1990s, when the visionary curator Joshua Compston collected explosives in his flat above his gallery on Charlotte Road. When they were discovered the police sealed off the street.

If arts and madness are often thought of as bedfellows, consider that by the end of the 17th century the term “Hoxton” was synonymous with madness. Several of the area’s larger houses had been turned into asylums for the insane. Hoxton House on Hoxton Street became the largest insane asylum in Hoxton in 1695 and lasted until as late as 1902.

With the rise of the suburbs during the early Victorian years, most of the more affluent residents left and much of the area turned to slums. Furniture and shoe factories sprang up. Theatres remained prominent. The enormous 3,000 seat Britannia Theatre was built on Hoxton Street. Charles Dickens attended performances there regularly. The building remained in place until 1941, but did not survive the Blitz. Another block of flats now stands in its place. Dickens drew plenty of inspiration from the area and its poverty. Much of Oliver Twist is set in Shoreditch.

Poor housing conditions lasted well into the 1930s, when the population of the East End reached its pre-war peak. After World War Two many families moved out to better accommodation, often in Essex. By the 1970s there were large numbers of abandoned homes and commercial premises in the area. Squatters occupied many of them.

Subscribe to the London Society newsletter

In the late 1980s artists started renting cheap studio spaces in former factories and warehouses. Designers and architects started to follow them. As professionals of all stripes started to pile in, estate agents realised there was money to be made. By the mid-1990s gentrification was well underway. Around the millennium the area became favoured by tech companies, and by the mid noughties Old Street had been given its alternative designation of Silicon Roundabout.

The YBAs themselves are mostly long gone, but gentrification is still unfolding in their wake. Even so, Hoxton and Shoreditch are now well established as an aspirational and expensive locale. Therein lies the irony. This is the first time in its history that it has ever been so thoroughly respectable. The outcasts, rebels and dreamers responsible for so much of its dramatic history are now firmly consigned to the past.

A conversation about artists, gentrification and property in London

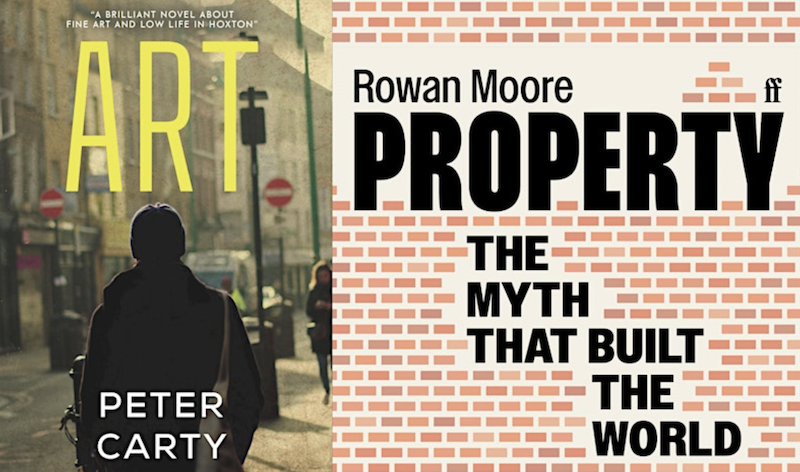

Peter Carty’s Art is published by Pegasus (£10.99). He will be in discussion about artists, gentrification and property with Rowan Moore, architecture critic of The Observer and author of Property: The Myth that Built the World (Faber, £14.99) at 7pm on Monday June 3rd at the Reference.Point bookshop, library, bar and cultural hub, 2 Arundel St WC2R 3DA (tickets £5, £4 concs). Click here for tickets.