Post

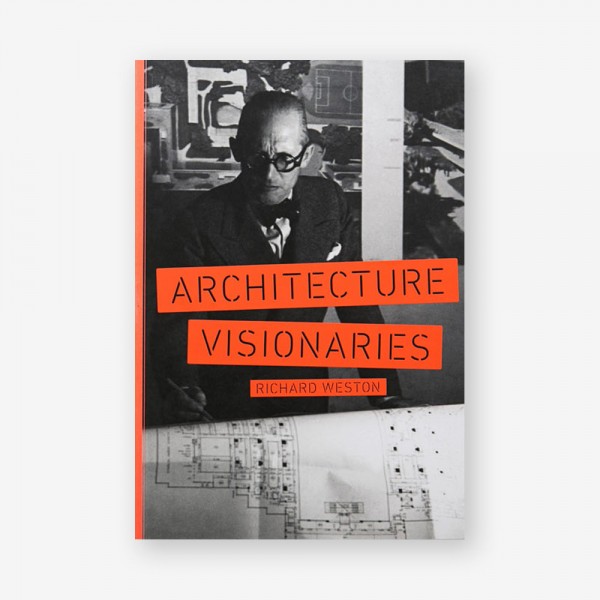

BOOK REVIEW | Architecture Visionaries by Richard Weston

7 Apr 2020

Architecture Visionaries by Richard Weston

Reviewed by Peter Murray

(This review appeared in the Journal of The London Society 468, Autumn/Winter 2015)

This 300-page tome collates the lives and work of the major international gures in 20th and 21st century architecture; it is comprehensive and well chosen, and includes six key London architects: Alison and Peter Smithson, James Stirling, Richard Rogers, Norman Foster and Zaha Hadid. The author, Richard Weston, is an eminent academic and architectural critic; his selection therefore prompted some thoughts on how well London responds to the visionaries in its midst.

Not too well, if we look at the work of the Smithsons. The bulldozers are poised to demolish their housing scheme at Robin Hood Gardens, completed in 1972 and generally agreed to be one of the most important examples of Brutalist architecture in the land. The destruction may yet be halted; a five-year immunity from heritage listing has just run out and the 20th Century Society is hoping that the Government will rethink and give the building protection from demolition.

The work of James Stirling at Number One Poultry in the City of London is threatened by alterations. Although the essential form of his replacement to the 19th century Mappin & Webb building remains unchanged, we must ensure the building is treated with respect; the capital is not oversupplied with work by a man who many consider Britain’s greatest architect of the latter half of the last century.

London is looking after Richard Rogers’ works rather better — his Lloyd’s Building was listed only 25 years after it was completed, making it the youngest Grade I structure in the country. It is very probable that the Gherkin, designed by Foster, will be listed in time, although by then it will be hidden among the gathering cluster of towers in the Square Mile.

There are a surprising number of non-British architects on Weston's list who have built in London. On his way to America from Nazi Germany, the former director of the Bauhaus, Walter Gropius, designed a house in Old Church Street in 1936, next door to another by Erich Mendelsohn.

Ralph Erskine, a Brit based in Sweden, designed the Ark in Hammersmith; Frank Gehry is currently working on an apartment building as part of the Battersea Power Station development; Renzo Piano has of course produced the Shard and colourful Central St Giles; while Tadao Ando built the elegant but minimal fountain outside the Connaught Hotel. Oscar Niemeyer, Toyo Ito and Peter Zumthor have done Serpentine Pavilions.

Zumthor’s was one of the most popular: a black box surrounding a herbaceous garden. Rem Koolhaas designed the Rothschild Building in the City of London and is currently completing a residential scheme for High Street Kensington, next to the new Design Museum. Daniel Libeskind’s sole London legacy is the London Met’s Graduate Centre, sitting uncomfortably on the Holloway Road. Courtesy of Tate Modern, Swiss architects Herzog & de Meuron seem quite at home here. Having converted the Bankside building they are now constructing Phase 2, a convoluted stack of bricks south of Gilbert Scott’s old power station.

To seal their commercial credentials, the firm has just received planning permission for a large and sculptural residential tower at Canary Wharf. Shigeru Ban has just landed his first UK project — a luxury housing development near Tower Bridge.

As with any list there are quibbles. I would have liked to have seen Sir Denys Lasdun, whose key London buildings — the Royal College of Physicians and the National Theatre — seem to get better and better with age. Since Steven Holl is there, why not Jean Nouvel and David Chipperfield? There are a few on the list that it would be nice to see building in London — Rafael Moneo, Eduardo Souto de Moura, Glenn Murcutt, and a permanent Zumthor.

That would give London a pretty full house of modern visionaries.