Post

BOOK REVIEW | Charles Booth's Poverty Maps

5 Dec 2019

Charles Booth's Poverty Maps

Thames & Hudson, £49.95

Reviewed by Jessica Cargill Thompson

For many members of the London Society, Charles Booth's Maps Descriptive of London Poverty will need little introduction. The intricate hand-coloured studies made at the end of the 19th century, in which each street of the capital is coded by socio-economic class, are not only an essential resource for historians and sociologists, the cause of endless hours evaporating as we look up our own streets and familiar stomping grounds.

So it is a thing of great joy that their custodians, the London School of Economics, has collected the core data together in a single volume that combines the high production values of art-book publisher Thames & Hudson, with new essays by 21st century scholars.

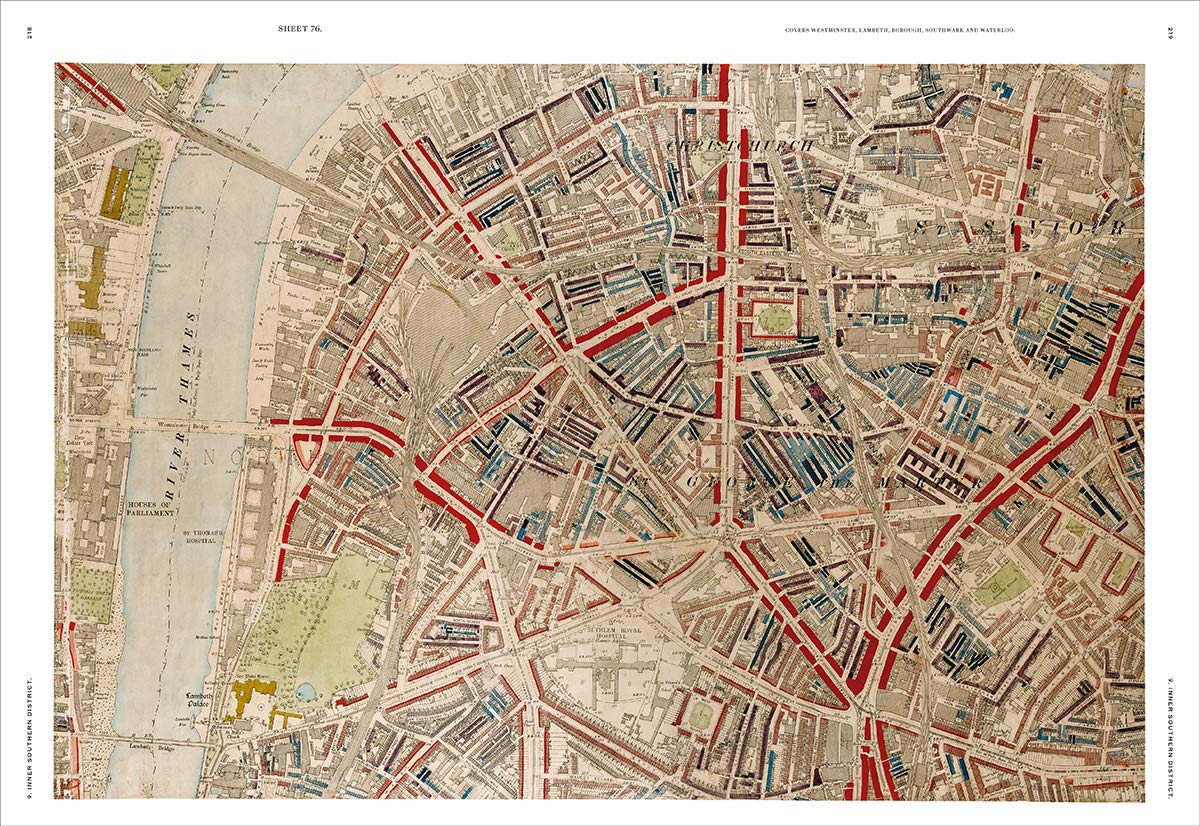

In his foreword, Iain Sinclair talks of the 'morbid beauty' of the maps, and they do indeed possess a corpse-like captivation. Booth's iconic colour scheme runs from the golden 'Wealthy', through vivid red of 'Middle class. Well-to-do', and the peachy 'Comfortable', to the ominous inky blue and black that signify 'chronic want' and 'vicious, semi-criminal'. Where streets and households were mixed (at the time some houses were occupied by three or more families), colours are blended into purples and browns. The effect is a city shot through with the red arteries of its mercantile high streets, yet pained by dark patches – Whitechapel, King's Cross, Bermondsey – that appear like bruises. Even the gilded halo of money around Hyde Park (Kensington, Mayfair, Marylebone) has its occasional splinters of back-street destitution.

Arguably the maps are the star thanks to their immediate visual impact and incredible level of detail, but they are the representation of some quite progressive sociological research analysing London's poverty, industry and religion. The 60 maps published here are from Booth's 1902-1903 Life and Labour of the People in London (1902-03), which in its original incarnation filled 17 volumes. This was the culmination of work that had begun in the 1880s, initially using information from local School Board Visitors, who were already obliged to assess the economic health of households with school-age children, before adopting more direct anthropological methods: accompanying policemen on their beat, observing street life, and interviewing employers and employees.

While 19th century writers such as Charles Dickens and Henry Mayhew had already drawn attention to the huge gap between the wealthiest and poorest Londoners, Booth – a steamship company owner acting out of personal philanthropic concern – and his team showed the full extent of the problem and exactly where it lived. By triangulating the economic position of households with factors such as employment security, health and family support, they were able to build up a richer understanding of society's underclasses. Indeed, the book reproduces a fantastic A-Z coding of the 'Causes of Pauperization', among them 'Absence or irregularity of work', 'Old Age, and 'Recklessness'.

Alongside the maps we get extracts from notebooks, bringing the everyday to life, as well as revealing the moral lens of the researchers: 'On Arcola Street, there is found to be a respectable looking coffee houses, which is in fact a well-known but low-class brothel'; 'Chester Mews is found to be a great corner for gambling.' We also eavesdrop on local tales, such as that of the costermonger who stabbed his wife then tried to hide the body by sewing it into a mattress, and stare back through the sepia mists of period photographs to proud street hawkers, beautifully curated shopfronts, car-free high streets, and community gatherings.

In addition to its physical presence (nearly 300 large-format pages bound in hardback) the book gains intellectual heft from essays giving 21st century relevance to Booth's key concerns. Prof Anne Power writing on housing draws parallels between the Victorian slum clearances that forced the low-waged into fewer and fewer streets where they faced greater competition for fewer places, with contemporary gentrification. Prof Mary S Morgan in the introduction warns of the effects of precarious employment, equating participants in today's growing gig economy with turn-of-the-century dock workers.

To really savour all that's on offer between these embossed covers would, one feels, take as long as it did Booth's researchers to compile. And still more riches lie in the LSE archives. For the legion of Booth-Map fans whose coffee tables this book will soon be adorning, that will be time well spent; for the uninitiated coming across these cartographical gems for the first time, including the friends from whose intrigued hands I've had to prize my own copy, this will be a wonderful introduction.