Post

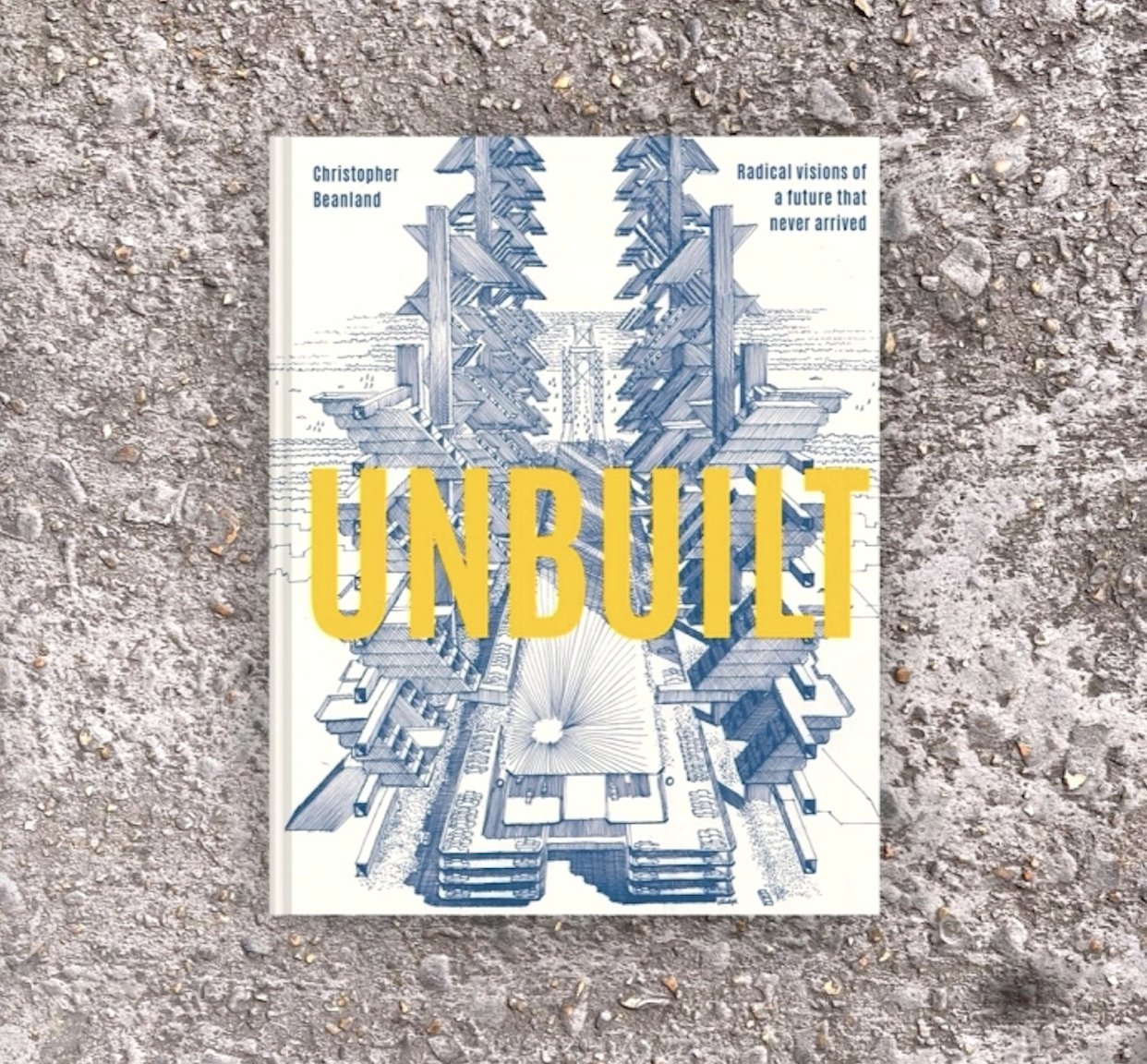

EVENT REPORT | Unbuilt - Radical visions of the future

11 Mar 2022

Event Review: Unbuilt - Radical visions of the future that never got built

With Christopher Beanland, Melodie Leung, Elain Harwood. Chaired by Rob Fiehn

Held at ING Media, Curtain Road EC2. 17 February 2022

The event began with a presentation by Christopher Beanland which narrated a series projects from around the world - though there was a variety of scales on display, they all shared a strong desire to break from the status quo.

Given that we're particularly interested in London, many of the projects shown were based there, but his recent book that shares the title of this talk, is more broad-ranging.

We began in Birmingham, looking at the post-war visions of John Madin and his contemporaries. A little closer to home - we looked at London’s 1938 plans for new orbital roads around the city. These were to be expansive roads, with 4 lanes in each direction, blasting through London’s urban centres like Camden, Brixton and Islington. Funding shortages meant it was only partly completed, the section which eventually became the Westway in the 1960s. Elain Harwood was quick to point out that though the building works did a lot of harm when the Westway cut through North Kensington, in some ways it was a catalyst for the formation of a whole new counterculture void.

The notion of ‘the parts that made it’, offered a nice segue into Brixton’s barrier block - built to house 2,500 people adjacent to a site earmarked for the construction of an elevated motorway. The motorway was never constructed - and so all that remains is an austere facade that is equally beguiling and domineering.

We looked at one of London's oddest transport proposals: an airport sited where King’s Cross station is today. The audience and panel were equally excited about the prospect of having a major airport right at the heart of the city, as we see in European cities. The question was posed whether London City Airport was technically an offshoot of this idea.

Staying with transport in London, we discussed the 2013 plans for Sky Cycle, a three-storey, 135-mile network of roads that would have been constructed above existing suburban rail lines to create new cycle routes throughout the capital. Though shelved we can draw conceptual links to contemporary near-equivalents like the Camden Highline and the Cycle Superhighways.

Further afield, Christopher quipped that grand visions tend to feature monorails everywhere. The office of Paul Rudolph had a penchant for a monorail, but also a knack for provocative pencil and graphene drawings that drew you in with their intricate detail. There was also a sense of ideas for their own sake in the projects of Archigram.

An interesting question was put to the panel and the audience: where is the infinite leisure time we were promised? Many utopian visions for the future featured boating lakes, open fields at the heart of the city or endless shopping arcades. The idea behind all of this was that, freed from work, we'd have more time to engage in social activities.

While abundant leisure time might not be a present reality, there is renewed focus on encouraging walking as a means of transit. In Sheffield, the 'hole in the road' roundabout was an early attempt to create separated levels for people and cars. The Barbican by Powell, Chamberlain and Bon also remains as an example of an intricately connected network of pedways, crisscrossing a large piece of the city.

The remainder of the evening was an engaged discussion between the panel and the audience, Melodie Leung of Zaha Hadid Architects reflected that the public still resonates with unbuilt projects because they capture the imagination. As a practice, Melodie observes that they are also captivated by the unbuilt. Ideas can be revisited later on and applied in new contexts, learning can be transferred to new projects, it all goes into the mixing pot to inform future projects.

The unbuilt work, Melodie said, also challenges them to maintain the level of boldness Zaha showed throughout her leadership of the practice; proposing inhabitable bridges or excavated monuments.

Elain riffed on the idea of grand visions, noting that in the sixties and seventies, we saw little pockets of grandeur. There was a real appetite for change at that time and fortuitously there were people in positions of power who wanted to do all they could to ‘improve’ society’s condition. For Elain, these 'pockets' are massively important, not only from an architectural point of view but historically. They help us to understand what culture and society were formerly like, for example, we didn't get the Fun Palace, but we got The Interaction Centre which was all about creating a space for people to come together.

Rob Fiehn, who was chairing the discussion, wanted to know where these grand visions come from. Melodie reflected that at ZHA, ideas come from a range of places, but mostly from mining their own back catalogue. They had spent so much time with Zaha that they developed an in-house language of experimentation. Beyond that the world is full of sources of inspiration, for example the hyperloop project isn't a massive leap from some of the utopic infrastructure projects we saw in the early 20th century.

Rob then pivoted to ask about the motivations behind these projects. Christopher wanted to point out that it wasn't solely opportunism, 'cheap rates' or post-war rebuilding, if we look at the plans for Manhattan or even London, the planners weren’t afraid to use demolition to get the space they wanted. So perhaps there may be an element of megalomania, but sometimes the impetus is genuinely to create spaces that are beguiling and attractive.

The question of how we're going to improve modern transport was next on the agenda. Clearly the 20th century had many leaders who wanted to push boundaries, where are we going to go from here? An audience member was quick to interject, the major infrastructure projects completed recently have been led by the private sector, Battersea, King’s Cross and the work on the Isle of dogs all follow the same mould - but another was happy to point out that Crossrail and HS2 are both government-led and vast in their scale. Predominantly though, the grand visions we see in the future are likely to be driven by commercial need or aspirations, unless the government finds a way of getting more inventive with finance, overcoming delays and their own double-mindedness.

Melodie Leung wanted to bring our attention to international case studies. ZHA has worked on several public transport schemes abroad, but nothing of a similar scale in the UK. Is it because of a lack of civic strength? According to Melodie, we need to drill down into recent failures, such as the wind-down of Brick by Brick so we can set a course for a new era of grand civic projects.

One of the audience asked a pointed question, do we really want to go back to the civic projects of the mid-20th century? They highlighted the failures on the Acorn and Aylesbury estates. Elain wasn't sure that we could make sweeping generalisations. The people of those communities were indeed let down, but that was more than an architecture issue, there were political and social issues at play too. Southwark had one of the most expansive social housing programmes in London and there is no question that a large number of people benefitted from that.

Distilling insight from the utopian visions of the past and with a hint of optimism for the future, the debate ended on the following note: people want views, they want light, they want their own sliver of the sky, therefore give us utopia, but make it human scale.