Post

Thames Tideway: How Thames Water will pay next to nothing for a £4billion tunnel

23 Aug 2024

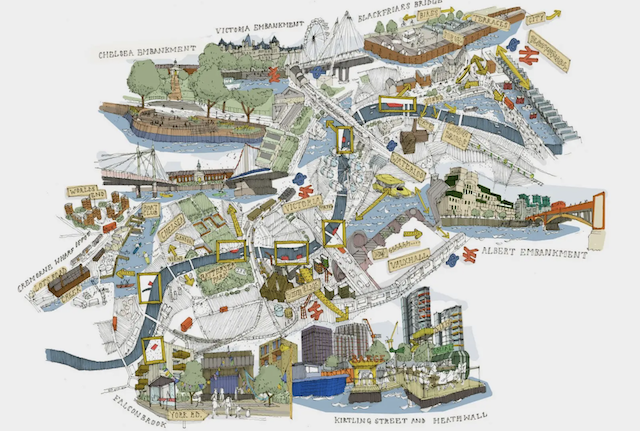

Come on our Thames Tideway walk

John Allen, The Open University and Michael Pryke, The Open University

London’s Victorian sewerage system is creaking and in dire need of renewal. The proposed solution: a 25km “super-sewer”, the Thames Tideway Tunnel, running from west to east across the capital at an estimated cost of £4.2 billion.

Thames Water wants to build the tunnel, but its owner, an international consortium of investors led by the Australian bank, Macquarie Group, has encountered a slight hitch: there’s not enough money to fund the upgrade. It seems there is too little equity left in the business and too much debt – the company has been leveraged up to the hilt, to the extent that it wants someone else to pay for the tunnel.

Can’t pay, won’t pay

In common with other investment consortia that own much of the water industry in England, Thames Water has been loaded up with debt since privatisation. The debt is now some £8 billion, amounting to around four-fifths of the business, a gearing of just under 80%.

In itself, such high leverage is not necessarily a problem, unless, that is, you want to borrow more money. Then you run the risk of damaging your credit rating. But the investors have a plan.

They’ve set up a separate business, a special-purpose vehicle, to deliver the tunnel, neatly sidestepping any credit rating concerns. But the cost of the tunnel renewal is to be effectively funded from household water bills, meaning an 11% increase for Thames Water’s 14m customers, up to 2020.

So, because it doesn’t have the money, Thames Water wants its customers to help pay for the super-sewer.

This is odd, perhaps, when you come to think about it. The privatisation of household water was sold to us in the 1980s as part of the wider Thatcherite drive to address the inefficiency of the public-sector providers by opening utilities to private-sector finance and management. The private sector was not slow in accepting the invitation. So what happened to all the finance and management?

Same water, different shareholders

In some ways, the water industry in England and Wales today looks much like it did at the time of privatisation in 1989. But after 25 years, only the trading names remain the same as before, with the public as a shareholder increasingly displaced by global consortia, pension and other specialist infrastructure funds.

Behind the familiar company logos, the companies that run Thames, Anglian, Southern and Yorkshire Water have led the way in engineering water bills for financial gain.

The asset that interests them, however, is not actually water, but people: households with the ability to pay water bills on a regular basis for the foreseeable future.

In the hands of a Macquarie-led consortium, such a guaranteed revenue stream presents a securitisation opportunity, that is, a means to package up a debt with the prospects of future revenue. Leveraging debt through securitisation allows revenue streams from underlying assets, in this case, Thames Water’s bill-paying customers, to be packaged together, bonds issued against them, and then sold on to investors.

Crucially, securitisation represents a claim against the cash that flows from household water bills in the future – a guarantee of money which customers have yet to be billed. It is a form of refinancing that leaves Thames Water’s balance sheet short of equity, but with a mound of leveraged debt.

Siphoning off profits

Of course, this debt could be used to lower household water bills or finance infrastructure development. But it may also be used to pay higher shareholder dividends.

Companies such as Thames Water, it turns out, have been paying out in dividends far more than they actually earn from their cash flows and using the borrowed money to fund substantial dividends for the best part of a decade – money that could have been used to finance the Thames Tideway Tunnel.

The structuring and crafting of such deals like this are a relatively new development, one which arrived after the onset of privatisation and which left the water regulator Ofwat in a position of having to adjust to the new financial reality.

Ring-fenced politics

Ofwat operates a regulatory ring-fence. So long as the water companies don’t allow their debt liabilities to interfere with their core water business, it’s pretty much left to them as to how much debt they take on. But the ring-fence, in the case of Thames Water, is looking as leaky as its decaying sewers.

The mound of debt taken on by Thames Water now means that it can’t raise the money to renew its infrastructure. Someone else – probably its bill-paying customers – will have to take on that burden.

If the political spotlight focused a little more brightly on the new financial reality of privatised water, you might get a reaction of the kind that has taken place in Berlin or in Copenhagen. The former has seen a re-municipalisation of water utilities, the latter protests against the machinations of Goldman Sachs in the Danish energy market.

We could do worse than take a look at Welsh Water’s not-for-profit model. With no shareholders, the money from household water bills goes towards financing new infrastructure development and, if there’s a surplus, towards the payment of an annual customer dividend. Thatcher, we suspect, might even have approved.

![]()

John Allen, Professor of Economic Geography, The Open University and Michael Pryke, Head of Geography, The Open University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.